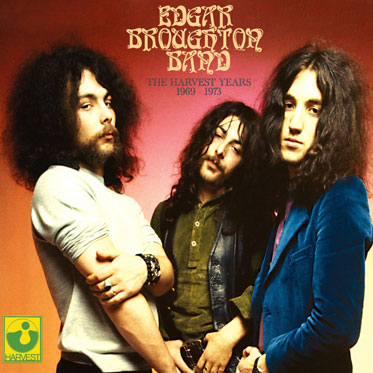

Edgar Broughton Band The Harvest Years (EMI 2010)

Initially forming in their native Warwick as The Edgar Broughton Blues Band in the burgeoning blues scene sweeping the UK during the 1960s, the power trio featured Robert “Edgar” Broughton on lead guitar and vocals, his brother Steve Broughton on drums and Arthur Grant on bass. They were later joined by a fourth member; guitarist Victor Unitt. Though Broughton brothers Steve and Rob had known Arthur Grant since they were small children, as young as five, how and when did they first come to play together as a musical unit?

STEVE BROUGTHON: We asked Arthur to join around his 16th birthday in 1966, and started doing gigs pretty soon after that. He lived just around a couple of corners!

EDGAR BROUGHTON: We had been playing blues for a while, and had two bass players thus far. Arthur was available and seemed more suitable than the current guy; cooler and a flashy dresser. Still is. Image was very important…we were all still getting to grips with our instruments…ha ha!

Relocating to London’s Notting Hill in 1968, which was fast becoming the capital’s psychedelic centre, they dropped “blues” from their name in the process, before drawing the attention of Blackhill Enterprises, management of the nascent Pink Floyd. This in turn led to a deal with EMI’s newly formed progressive imprint, Harvest Records. Was there a feeling of being at the centre of something special or important, in swinging London?

SB: Absolutely. We were staying in a two bedroom, 3rd floor flat at Colville Terrace off the Portobello Road with three student friends who were already sharing the two bedrooms. It was mayhem, watching psychedelic lightshows on the walls opposite our flat. It was also the place where my daughter Sally was designed, earlier that year. All Saints Hall was round the corner, with Floyd, the Deviants or Tyrannosaurs Rex playing there every week. We couldn’t have landed anywhere better.

EB: London was like another country compared to Warwick; the mix of people, culture and food. I tasted my first Jamaican food around the corner, in Portobello Road. Everywhere we went there was something exciting happening; new fusions of music, ideas, politics and art. There is no doubt that a really strong community spirit flourished in the All Saints area. We were like kids in a sweet shop.

Harvest was formed in 1969 to compete with other major label owned progressive imprints such as Decca’s Deram, and later Pye’s Dawn and Philips’ Vertigo. Auspiciously, the Edgar Broughton Band’s debut 45 ‘Evil’ was released as Harvest’s first single in June 1969, soon to become label mates with such luminaries as Pink Floyd, Deep Purple and the Electric Light Orchestra. How much artistic and creative freedom and independence was the band afforded?

SB: Total really; no one understood us! Better to just agree.

EB: Quite a lot. Peter Jenner had to put his foot down on occasion, when faced with some of our musical excesses or psychedelic meanders, but we more or less made what we wanted. It’s clear that a signing of our status back then would not get that freedom today.

Influenced by everyone from Captain Beefheart to The Shadows, sometimes within the same song, where else did you take influences from? Were you aware of the proto-punk, metal and garage bands in the States, such as Blue Cheer, MC5 and The Stooges?

SB: Any musician with their ears open will be influenced by whatever they hear. Certainly we were lumped in with MC5 by the press of the era. I never got the similarity myself! Blue Cheer were just totally, incredibly, fucking loud, and Iggy has ended up doing car insurance ads on telly????!! So no, not really.

EB: I knew of The Stooges, and MC5 of course, but we didn’t take much notice of what they were doing. I think we were UK Proto punk.

Who did you share the most enjoyable touring and gigging experience with?

EB: Many of the Blackhill bands of that time were fun to be with. We got to know the Kevin Ayers guys well, Formerly Fat Harry, who were very nice, and Floyd, who were always friendly if a little “straight” in the parlance of the day. The Moody Blues were one of the warmest bunch of guys I ever met. Being in the EBB was the best part of it. We had a lot of fun and adventures most of the time, and quickly recovered from set backs together. We were a band of brothers.

You seemed keen on playing for free, and felt everyone else should follow suit, which wasn’t appreciated by all quarters of the music industry.

SB: No, we didn’t feel everyone else should, we believed then, and still do, in the freedom to choose outside the box, and not to conform within it, which is unfortunately what many people are bound to do. If you need to understand what the buzz is of playing music for free, especially to a big crowd, try it some time. It took the music industry a while to understand the power of free concerts. Now it’s the norm for bands to appear for free; the Stones at Copacabana beach for 2 million people. Wicked!

EB: It’s not that we thought every one else should follow suit, but maybe make the odd concession to always getting paid. It’s good for the soul to make a contribution, and many of the free music detractors could easily have afforded to participate on an occasional basis. I think all kinds of music biz folk and bands were afraid we might undermine their livelihoods. As if!

You certainly had a political stance, and certainly gave the impression of being at odds with society.

EB: Not at odds with society exactly, though there were and still are Kafkaesque aspects of living in the UK that should be addressed immediately. At a free concert every one can have some. If only this were true for people on the fringes of this society. Years of political abuse by government and their destruction of rights we held dear back then has led us to the place we are now. For the weak and vulnerable this is a disaster. I still advocate a level playing field with equal opportunity and access for all. It’s all down to my upbringing I am happy to say.

SB: We had grown up in the 50s, and experienced the tail end of all those authoritarian, post-war values, and then, moving on into the 60′s era of political radicalisation and drugs and free love, it was natural that the band would reflect those experiences. We were educated working class kids who wanted out, certainly of Warwick!

The band was highly influential, but never received their full due.

EB: I think the EBB was a difficult thing to manage, and yet at the same time in some ways it was better for it. Unintentionally, we alienated people who expected us to do what they wanted. The whole point of being in the band was that we didn’t do that unless it fitted our ethos. We have to accept that a life and a life’s work cannot be measured simply in terms of record sales, nor even applause. I hope our influence has been mostly positive. We are all still around, we are healthy and reasonably safe and sane, and it ain’t over until the Rubenesque woman sings. I have few regrets if any, and none that haunt me.

On 7th June 1969, the band appeared at Hyde Park festival headlined by super-group Blind Faith, returning on 20th September the same year for a bill headlined by Soft Machine. The Edgar Broughton Band’s third appearance at Hyde Park was on 18th July 1970 on a bill featuring fellow Harvest luminaries Roy Harper, Kevin Ayers, and headlined by Pink Floyd. The previously unreleased recording of that appearance appears here for the first time, mastered at Abbey Road by Peter Mew (who engineered many of their original recordings), and under the supervision of the band themselves. Their 45 minute set is faithfully reproduced here in all its raw and raucous glory. What are your memories from playing at Hyde Park? The crowd seemed to really enjoy it.

SB: It was great……………..I think!!!!!!!!!

EB: I remember being very scared. The audience was huge, but very warm. Cranked up Marshall valve amps crunching out across the park. Charlie Watkins, with his huge Wall of sound PA. A big noise seemingly over in a flash. A band/family adventure of immense significance. Signing dozens of autographs for the first time whilst walking back through Piccadilly.

Is that Edgar’s guitar getting trashed at the end of Out Demons Out?

EB: Yes, but strangely that old Strat never got really smashed up. It was hand built like a tank by Leo Fender himself. I paid fifty quid for it second hand in about 1965. It has many battle scars, but I still have it and have often played it on live shows from then until now.

The Edgar Broughton Band released five studio albums for Harvest, from 1969’s Wasa Wasa, Sing Brother Sing (1970), the eponymous Edgar Broughton Band (1971) and Inside Out (1972) through to Oora in 1973. What led to you parting with the label?

SB: Basically a change of management. Probably not the best decision we ever made, but a decision nonetheless.

EB: It might have been something to do with the reprobates who were managing us at the time.

The band carried on for a handful of albums for a number of labels, and even reformed the original line-up in 2007. Do you have fond memories of the late sixties and early seventies on Harvest?

SB: Yeah!

EB: The sixties / seventies were when I was growing up, having a ball, so I don’t know if I would have cared who signed us. It would have been a euphoric moment in any case but Harvest did offer a unique opportunity for bands like us. They took a risk and, for the most part, they stuck with it. Abbey Road and it’s boffins in techie coats bearing new fangled tools such as phasers and multitap echo gadgets, with the inimitable Pete Mew and others. Amazing! It’s just a shame our royalties were so criminally low…and still are haha!

Notes by Hugh Gilmour

London 2011

with thanks to Arthur Grant, Steve Broughton and Rob Broughton